THE FLORENCE STOCKADE: A CIVIL WAR PRISON CAMP HELL IN SOUTH CAROLINA

How A Hellish South Carolina Civil War Concentration Camp, Complete With Mass Graves, Became A National Cemetery That Helped A Community Heal Afterward

Tucked away in a corner of Florence, South Carolina, sits a quiet patch of land you have to be looking for to find. The Florence National Cemetery can be found on its namesake road, now a place of silent meditation among hanging moss, prayer, and remembrance for those who have passed. But the origins of this peaceful sanctuary were nothing like its present calm. The foundation was laid with a violent, chaotic, and grim series of events that took place between 1864 and 1865. This cemetery isn’t just a place where soldiers were laid to rest—it’s a place where they starved, suffered, and were murdered in cold blood. A place where, in the final desperate months of the Confederacy, Union prisoners were crammed behind pine-log walls and treated no different than barn animals. Even in death, many of them were shown no respect at all at the time.

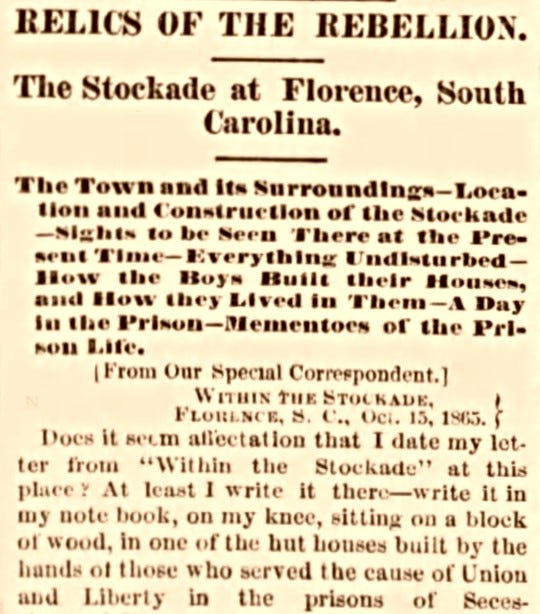

The story begins not in Florence, but in Georgia, at the infamous Andersonville Prison. By the summer of 1864, with Sherman’s army bearing down on Atlanta, Confederate leaders feared their Andersonville prison camp would soon be overrun and its tens of thousands of prisoners freed. In a desperate effort to prevent this, the Confederate army and civic authorities evacuated thousands of Union soldiers northward. Arriving first in Charleston, many of the prisoners would be housed at the former Horse Track, now known as Hampton Park, and at Castle Pinkney in the harbor. Most would continue on to Florence, a small railroad hub in the Pee Dee region. Florence was ultimately chosen as the primary relocation site due to its access to rail lines and its distance from Sherman’s advance. Within weeks, what had been little more than a sleepy depot town became the site of a hastily constructed Confederate prison camp.

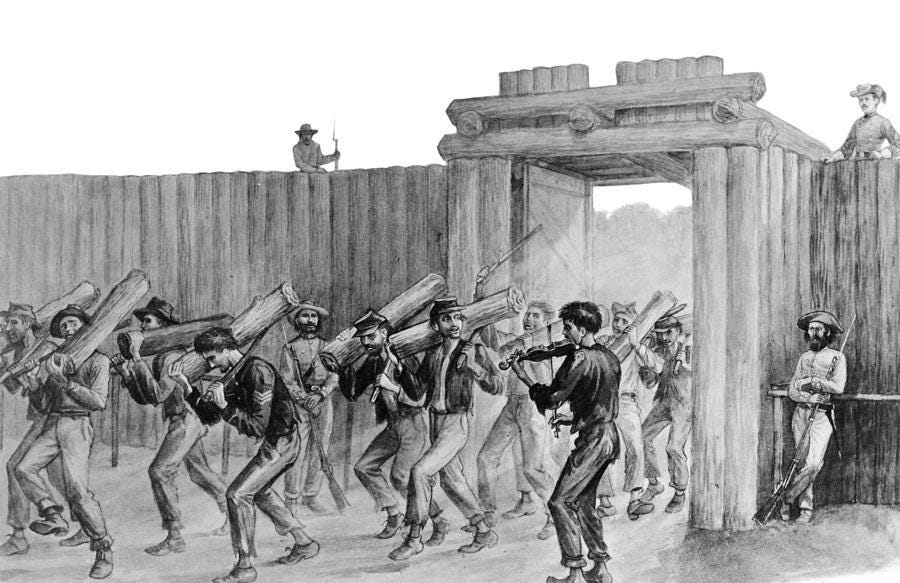

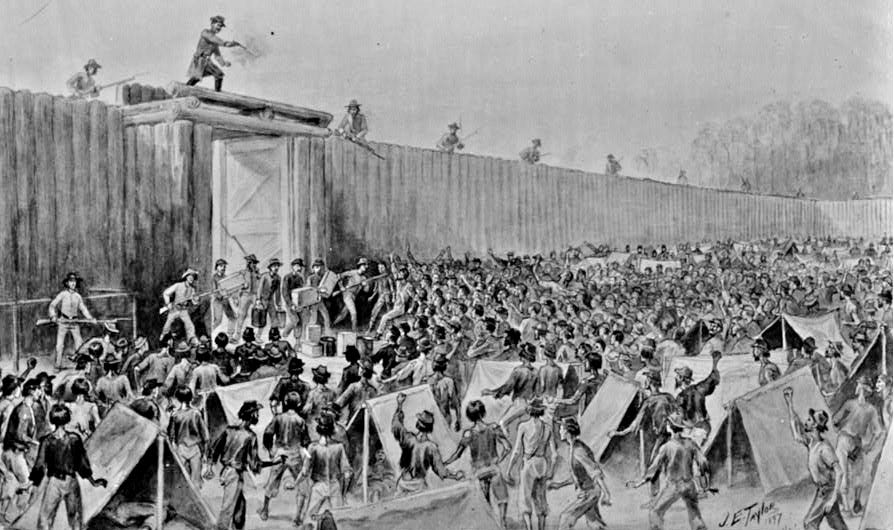

Construction of the Florence Stockade began in September 1864. Confederate engineers, with the help of slaves from local plantations, quickly built a 23-acre wooden enclosure made of pine logs. The first trainloads of prisoners began arriving later that month, many of them already emaciated and sick after enduring the horrors of Andersonville and the trip north. The three-day journey in cramped, filthy boxcars only served to make the prisoners situation worse. Initially, prisoners slept under guard in an open field while they were forced during the day to complete the walls of their unfinished prison. Some 8,000 men arrived before the camp was ready, resulting in escape attempts and prisoners being gunned down according to survivor accounts.

Once inside, conditions rapidly deteriorated. The Florence Stockade had no shelter, leaving prisoners to dig holes in the ground or built makeshift huts out of scraps of cloth and pine branches. A small stream known as Pye Branch ran through the camp dividing it roughly in two. This shallow creek served as drinking water, bath, and outhouse for the prisoners—quickly becoming contaminated and disease-ridden. The guards, many of whom were old men or teenage boys from nearby Florence, were overwhelmed and poorly supplied themselves, never having intended to participate in the situation.

By October 1864, more than 12,000 Union prisoners were crammed into the Florence Stockade. The death rate soared. According to John McElroy, a former prisoner who later published a memoir of his experience, the conditions in Florence were even worse than those at Andersonville. Food was scarce—often just raw cornmeal—and medical supplies were almost nonexistent. Disease ran rampant, with dysentery, pneumonia, and scurvy claiming the lives of 20 to 30 men a day.

The local community of Florence was deeply affected by the presence of the prison. A town of only a few dozen structures, Florence struggled to accommodate the sudden influx of prisoners, guards, and Confederate officials accompanying it. Local resources were strained as the Confederate army requisitioned food and supplies to support the camp. Civilians were warned to avoid the area due to fears of disease, or escapees, but some residents— most notably enslaved African Americans and local women— would attempt to throw food over the walls unnoticed in the night.

Survivor accounts paint a chilling picture of life and death inside the stockade. Sgt. Robert H. Kellogg of the 16th Connecticut described seeing men reduced to skin and bone, barely clothed, crawling through the dirt in search of roots to eat. Others recalled being beaten or shot for approaching the camp’s "dead line," a boundary near the walls that prisoners were forbidden to cross. Guards, particularly Lt. James Barrett, were accused of extreme brutality, with Barrett allegedly shooting prisoners for sport and mocking the suffering of the Union men. One account claims Barrett killed a prisoner once, shooting him in the head at point blank range, for telling Barrett “The war is over. You lost”.

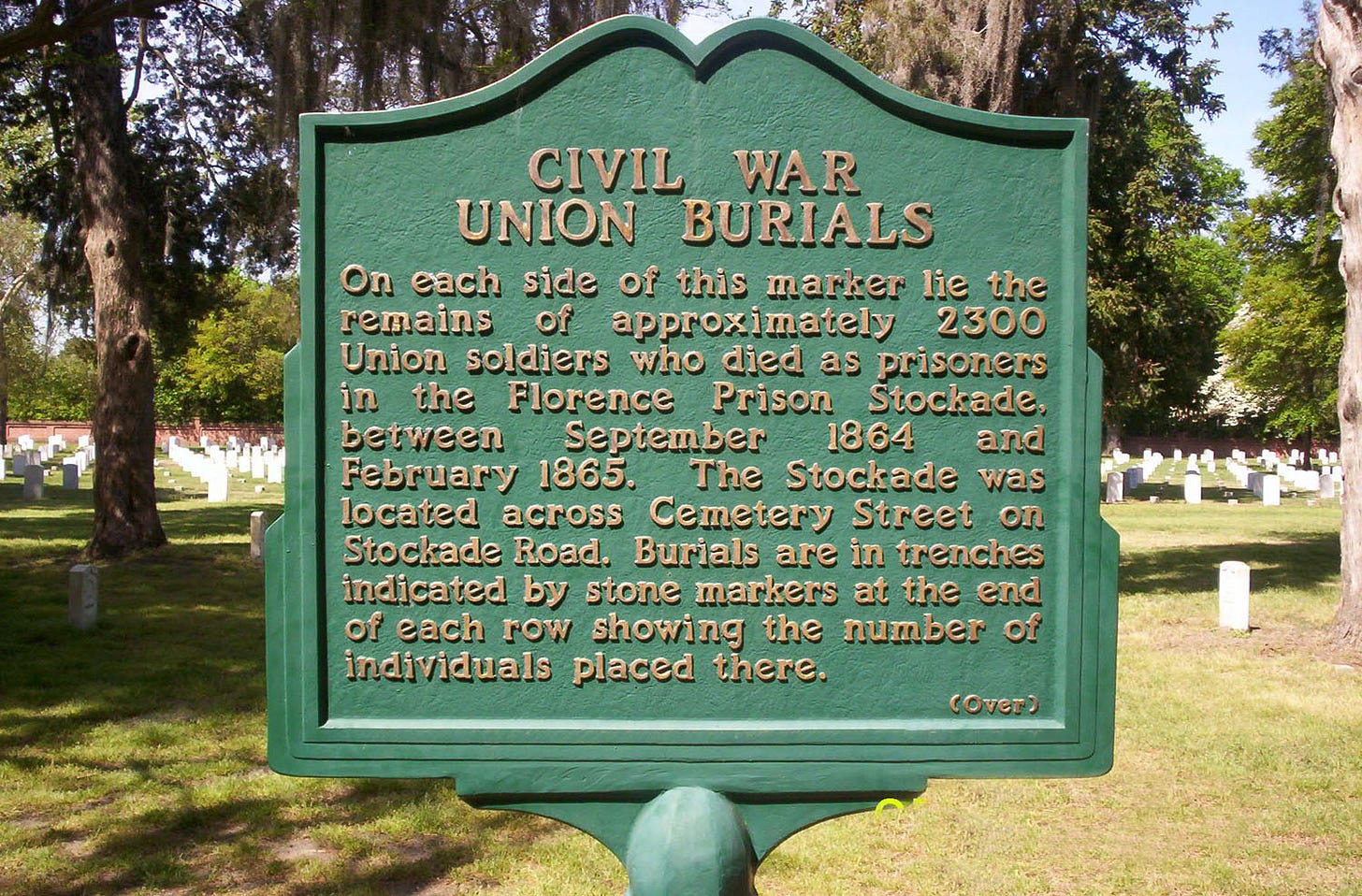

As Sherman’s army marched north through South Carolina in early 1865, the Confederate authorities began to evacuate the Florence Stockade as well. Thousands of prisoners were transferred to other locations, while the sick and dying were left behind or taken to makeshift hospitals in Florence. The dead from the Florence Stockade were buried in mass trenches just outside the camp. Some prisoners were forced to bury their comrades in unmarked mass graves that were mockingly called “Republican Cradles” by Confederate guards. After the war, the Federal authorities made efforts to properly mark the graves, and the burial grounds were converted into the Florence National Cemetery. Thousands of Union soldiers are now buried there, most in marked graves, though many remain unknown, marked with only numbers.

One notable grave belongs to Florena Budwin, the first female soldier buried in a U.S. national cemetery. Florena disguised herself as a man in order to follow her husband into the Union Army. Their unit would be captured and sent to Andersonville, where her husband would die, but her secret would remain. Her identity wasn’t discovered until she fell ill in Florence, where she would ultimately die. Upon treating her for pneumonia a doctor would discover her sex. Her story, along with those of thousands of others who passed through the Florence Stockade, serves as a reminder of the human cost of war.

Though the Florence Stockade never gained the infamy of Andersonville, the suffering that occurred there was just as real. Nearly 3,000 Union prisoners died in Florence over the course of five brutal months. Only a few Confederate officers were held accountable for what happened. Most, like Lt. Barrett, escaped judgment entirely. Today, the site is preserved as both a national cemetery and a historical landmark, a tribute to the lives lost and a sobering reminder of what unchecked cruelty and war can do.

Visitors to the Florence National Cemetery walk over the same ground where men once starved, froze, and died. The neatly aligned headstones offer little hint of the suffering that took place there, but the story lives on in historical records, survivor testimony, and the preserved earthworks of the old stockade. In remembering that past, South Carolinians—and Americans more broadly—can honor the dead not just with stone, but with truth.

Now the ground that was once home to groans of starving men, the collapse of the dying, the agonies of a war —now only peaceful silence. Here, where Americans once unleashed cruel brutality on one another, Americans now kneel in united grace. They mourn the known and unknown alike, not only their kin but every soul who ever bore the burden of the uniform. This hallowed ground, baptized in blood, has become a place where the wounds of history are healed by the promise that such sacrifice will never be forgotten—and that America, still, stands united.